No Luck

No luck. You rolled a 404.

A list of all the posts and pages found on the site. For you robots out there is an XML version available for digesting as well.

No luck. You rolled a 404.

About me

This is a page not in th emain menu

Have you been struggling with formatting examples, tables and cross-references in your dissertation? Curious if there’s a better way? Here’s a gentle introduction to using LaTeX.

Have you been struggling with formatting examples, tables and cross-references in your dissertation? Curious if there’s a better way? Here’s a gentle introduction to using LaTeX.

Looking for guidance on how to use video in language documentation? A new paper by Mandana Seyfeddinipur and Felix Rau provides some tips.

The folks over at the Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America have developed a training course in digital language archiving. It’s called Archiving for the Future, and it breaks down the process is simple, easy to follow steps.

The folks over at the Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America have developed a training course in digital language archiving. It’s called Archiving for the Future, and it breaks down the process is simple, easy to follow steps.

Looking for digital sources on Papuan languages? Here are a few places to start.

Here’s a useful collection of materials for doing language documentation and typological field work.

Short description of portfolio item number 1

Short description of portfolio item number 2

PLoS ONE [more info]

Citation: Sicoli, Mark and Gary Holton. 2014. Linguistic phylogenies support back-migration from Beringia to Asia. PLoS ONE 9(3): e91722. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0091722]

Oceanic Linguistics [more info]

Citation: Holton, Gary, Calistus Hachibmai, Ali Haleyalur, Jerry Lipka, and Donald Rubinstein. 2015. East is not a ‘big bird’: The etymology of the star Altair in the Carolinian sidereal compass. Oceanic Linguistics 54(2).579-588 http://doi.org/10.1353/ol.2015.0021

The Languages and Linguistics of the New Guinea Area: A Comprehensive Guide

Citation: Holton, Gary and Marian Klamer. 2017. The Papuan Languages of East Nusantara. The Languages and Linguistics of the New Guinea Area: A Comprehensive Guide, ed. by Bill Palmer, 569-640. (The World of Linguistics, vol. 4.) Berlin: Mouton.

NUSA [more info]

Citation: Holton, Gary. 2017. A unified system of spatial orientation in the Austronesian and non-Austronesian languages of Halmahera. Language Contact and Substrate in Wallacea, ed. by Antoinette Schapper. NUSA 62.159-91. http://hdl.handle.net/10108/89846

Oxford Handbook of Endangered Languages

Citation: Holton, Gary. 2018. Interdisciplinary language documentation. Oxford Handbook of Endangered Languages, ed. by Kenneth Rehg and Lyle Campbell. Oxford University Press. http://gmholton.github.io/files/holton-2018-interdisciplinary.pdf

University of Hawai‘i Press [more info]

Citation: McDonnell, Bradley, Andrea Berez-Kroeker, and Gary Holton. 2018. Reflections on Language Documentation 20 Years After Himmelmann 1998. (Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication no. 15.) Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. https://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/sp-15/

University of Hawai‘i Press [more info]

Citation: Holton, Gary and Thomas F. Thornton. 2019. Language and Toponymy in Alaska and Beyond. Fairbanks and Honolulu: Alaska Native Language Center and University of Hawai‘i Press. https://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/sp-17/

The Languages and Linguistics of North America: A Comprehensive Guide

Citation: Holton, Gary and Andrea L. Berez-Kroeker. to appear. Sens of place in North America. The Languages and Linguistics of North America: A Comprehensive Guide, ed. by Carmen Jany, Marianne Mithun, Keren Rice. Mouton de Gruyter.

The Oxford Guide to the Malayo-Polynesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar

Citation: Pappas, Leah and Gary Holton. to appear. Spatial orientation in the Malayo-Polynesian languages outside Oceanic. The Oxford Guide to the Malayo-Polynesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar, ed. by Sander Adelaar and Antoinette Schapper. Oxford University Press.

Open Handbook of Linguistic Data Management [more info]

Citation: Holton, Gary, Wesley Y. Leonard, and Peter L. Pulsifer. 2021. People, ethics, and data. Open Handbook of Linguistic Data Management, ed. by Andrea Berez-Kroeker, Bradley McDonnell, Eve Koller, and Lauren Collister. Cambridbge: MIT Press. http://gmholton.github.io/files/581-92248_ch04_1P.pdf

Linguistics Vanguard [more info]

Citation: Pappas, Leah and Gary Holton. 2022. A quantitative approach to sociotopography in Austronesian languages. Linguistics Vanguard 8(1).11-23. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2020-0044

Memory and Landscape [more info]

Citation: Holton, Gary. 2022. Place naming strategies in Inuit-Yupik and Dene languages in Alaska. In Kenneth L. Pratt & Scott Heyes (eds.), Memory and Landscape: Indigenous Responses to a Changing North, 276–296. Athabasca: Athabasca University Press. holton-2022-place_naming.pdf

Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 1: Introduction [more info]

Citation: Holton, Gary. 2022. Digital Domains for Native American Languages. In Igor Krupnik (ed.), Hanbook of North American Indians, Vol. 1: Introduction, 211-229. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. http://gmholton.github.io/files/holton-2022-digital_domains.pdf

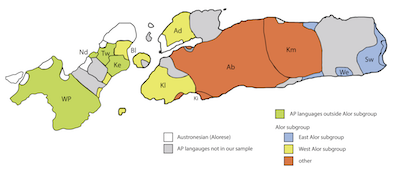

Origins of the Alor-Pantar Languages</a> (2009-2016) is an NSF-funded project which seeks to unravel the linguistic prehistory of the non-Austronesian (Papuan) languages the of Alor-Pantar archipelago of southeastern Indonesia. This international project, conducted under the aegis of the European Science Foundation EuroBABEL programme, has vastly increased our knowledge of the previously under-documented Alor-Pantar language family. A volume of papers detailing the results of this project was published in 2014 (revised 2017) as The Alor-Pantar Languages: History and Typology</a> (Marian Klamer, ed.). This volume was published through Language Sciences Press, a new open-access, peer-reviewed venue; hence, the individual papers can be freely downloaded.

Origins of the Alor-Pantar Languages</a> (2009-2016) is an NSF-funded project which seeks to unravel the linguistic prehistory of the non-Austronesian (Papuan) languages the of Alor-Pantar archipelago of southeastern Indonesia. This international project, conducted under the aegis of the European Science Foundation EuroBABEL programme, has vastly increased our knowledge of the previously under-documented Alor-Pantar language family. A volume of papers detailing the results of this project was published in 2014 (revised 2017) as The Alor-Pantar Languages: History and Typology</a> (Marian Klamer, ed.). This volume was published through Language Sciences Press, a new open-access, peer-reviewed venue; hence, the individual papers can be freely downloaded.

The Alaska Native Place Names Project collaborates with Indigenous communities across Alaska to consolidate Indigenous place name documentation and related linguistic, cultural and environmental knowledge.

The Alaska Native Place Names Project collaborates with Indigenous communities across Alaska to consolidate Indigenous place name documentation and related linguistic, cultural and environmental knowledge.

The endangered languages crisis is widely acknowledged as one of the most pressing problems facing humanity today, posing moral, practical, and scientific issues of enormous proportions. The Catalogue of Endangered Languages (ELCat) represents the first fully reliable source dedicated to the endangered languages of the world. Founded in 2012, the Catalogue provides authoritative information on language status and vitality, informs users about the plight of endangered languages, and encourages efforts to slow the loss.

The endangered languages crisis is widely acknowledged as one of the most pressing problems facing humanity today, posing moral, practical, and scientific issues of enormous proportions. The Catalogue of Endangered Languages (ELCat) represents the first fully reliable source dedicated to the endangered languages of the world. Founded in 2012, the Catalogue provides authoritative information on language status and vitality, informs users about the plight of endangered languages, and encourages efforts to slow the loss.

The Kaipumakani Project supports the development of a Mukurtu Hub for Hawai‘i and the Pacific, as part of Mukurtu Hubs & Spokes, an IMLS National Leadership Grant to Washington State University. This project will develop the next generation of the Mukurtu CMS and facilitate digital cultural heritage preservation in the Pacific. (http://kaipumakani.org)

The Kaipumakani Project supports the development of a Mukurtu Hub for Hawai‘i and the Pacific, as part of Mukurtu Hubs & Spokes, an IMLS National Leadership Grant to Washington State University. This project will develop the next generation of the Mukurtu CMS and facilitate digital cultural heritage preservation in the Pacific. (http://kaipumakani.org)

The MEaCoM project convenes a series of workshop bringing together key stakeholders including linguists, archivists, and software developers to develop a software requirements specification and associated use cases (or “user stories”) for a metadata and collection management tool. A beta version, dubbed laMeta, was released in March 2020 and is freely available for download.

The MEaCoM project convenes a series of workshop bringing together key stakeholders including linguists, archivists, and software developers to develop a software requirements specification and associated use cases (or “user stories”) for a metadata and collection management tool. A beta version, dubbed laMeta, was released in March 2020 and is freely available for download.

The Austronesian languages are well-known for the prevalence of geocentric systems of spatial orientation which use geography rather than ego as a reference point—most notably the distinction between ‘seaward’ and ‘landward’ This basic system has deep antiquity and can be reconstructed for Proto-Austronesian.

Gary Holton and Leah Pappas

This paper presents the results of a survey of spatial orientation systems across the Malayo-Polynesian languages outside the Oceanic branch. Although spatial orientation has been studied extensively in Oceanic languages, relatively less attention has been paid to orientation in the non-Oceanic languages. Drawing on recent surveys (e.g., Gallego 2018), reference grammars, and original field work, we delineate three broad types of spatial orientation systems: cardinal, elevation-based, and water-based.

Elevation-based systems are more commonly found in the non-Austronesian languages of the region but can be found also in some Central Malayo-Polynesian languages. Water-based systems in turn include two types: coastal systems which contrast a seaward-landward axis with an orthogonal axis parallel to the coast; and riverine systems which contrast an upriver-downriver axis with an orthogonal toward vs. away from river axis. In the coastal systems the seaward-landward axis is determined by local geography, but the coastal axis is essentially fixed, as in Oceanic (cf. François 2004). In contrast, in the riverine systems both axes are geographically determined; neither is fixed. In particular, the orientation of the upstream-downstream axis is readily determined by the direction of current flow, obviating the need to appeal to post-hoc social explanation for the orientation of the up-down axis (cf. Holton 2017). Cardinal systems—in which two orthogonal axes are essentially fixed—predominate in the west, reflecting a general tendency towards more cardinal systems as one proceeds east to west through the archipelago.

In a number of languages the coastal and riverine systems coincide, suggesting that such coastal systems may have their origins in originally riverine systems. Moreover, such languages are broadly distributed both geographically (Borneo, Maluku, Philippines, New Guinea) and genetically (Greater North Borneo, Greater Central Philippines, South Sulawesi, South Halmahera-West New Guinea, Trans-New Guinea, West Papuan) across the region, suggesting a wider pattern of riverine directionals which may predate the Austronesian expansion (as previously suggested for Halmahera in Palmer 2002: 149).

Nearly three decades ago in Chicago, Ken Hale and other perceptive LSA members identified a crisis within the discipline of linguistics, warning that the field risked becoming “the only science that presided obliviously over the disappearance of 90% of the very field to which it is dedicated” (Krauss 1992:10). The response has been both global and paradigm-shifting, leading to a renewed focus on language documentation and language reclamation. There is no doubt that the National Science Foundation Documenting Endangered Languages (DEL) program has been central to that effort. Not only has DEL provided direct support for documentation efforts, it has also contributed to capacity building; the development of new tools for documentation; and the adoption of new approaches to documentation. As we reflect on 15 years of DEL funding, two important questions emerge. First, to what degree has a distinct DEL program contributed to the successful response to the endangered languages crisis? Specifically, could this effort have been equally-well achieved directly within existing NSF programs? Even if we answer this question in the affirmative, there remains a second, perhaps more relevant, question. Namely, is a distinct DEL program still useful? In other words, has the DEL program now achieved its intended purpose and outlived its usefulness as a distinct program?

This second question is less heretical than it might first appear. The success of the DEL program has led to an increased awareness of endangered languages across the entire field of linguistics. It is no longer unusual for a theoretician to engage in field work, and few field workers now ignore the plight of language loss within indigenous communities where they work. DEL-funded efforts such as the Austin Principles of Data Citation in Linguistics (Berez-Kroeker et al. 2018) promote increased citations of primary data in linguistics publications. No longer a fringe topic, endangered language documentation and reclamation are now part of the fabric of the discipline of linguistics. So it is not unreasonable to argue that while DEL may have once been useful, the changes in the field over the last three decades have made the need for a distinct funding program less compelling.

In this paper I argue that the answer to both of the questions posed above is “no.” Drawing on examples from several DEL-funded projects I show that at least in some cases DEL projects would have been unlikely candidates for NSF support without a dedicated funding stream. I then review key features of DEL which distinguish it both from the Linguistics program and from other programs with NSF, showing that the innovations facilitated by DEL are largely unique to this program and not replicated elsewhere within NSF, nor in other funding agencies (cf. Holton and Seyfeddinipur 2018). Extrapolating from these examples I conclude that there is still a need for a distinct DEL program. Whether or not the world’s languages are still in crisis, there remains much work to be done. We are far from completing the work of documenting the world’s languages; there is still great need for new tools and infrastructure for language documentation; and there is much yet to do to build capacity for undertaking documentation work.

Nearly three decades ago in Chicago, Ken Hale and other perceptive LSA members identified a crisis within the discipline of linguistics, warning that the field risked becoming “the only science that presided obliviously over the disappearance of 90% of the very field to which it is dedicated” (Krauss 1992:10). The response has been both global and paradigm-shifting, leading to a renewed focus on language documentation and language reclamation. There is no doubt that the National Science Foundation Documenting Endangered Languages (DEL) program has been central to that effort. Not only has DEL provided direct support for documentation efforts, it has also contributed to capacity building; the development of new tools for documentation; and the adoption of new approaches to documentation. As we reflect on 15 years of DEL funding, two important questions emerge. First, to what degree has a distinct DEL program contributed to the successful response to the endangered languages crisis? Specifically, could this effort have been equally-well achieved directly within existing NSF programs? Even if we answer this question in the affirmative, there remains a second, perhaps more relevant, question. Namely, is a distinct DEL program still useful? In other words, has the DEL program now achieved its intended purpose and outlived its usefulness as a distinct program?

This second question is less heretical than it might first appear. The success of the DEL program has led to an increased awareness of endangered languages across the entire field of linguistics. It is no longer unusual for a theoretician to engage in field work, and few field workers now ignore the plight of language loss within indigenous communities where they work. DEL-funded efforts such as the Austin Principles of Data Citation in Linguistics (Berez-Kroeker et al. 2018) promote increased citations of primary data in linguistics publications. No longer a fringe topic, endangered language documentation and reclamation are now part of the fabric of the discipline of linguistics. So it is not unreasonable to argue that while DEL may have once been useful, the changes in the field over the last three decades have made the need for a distinct funding program less compelling.

In this paper I argue that the answer to both of the questions posed above is “no.” Drawing on examples from several DEL-funded projects I show that at least in some cases DEL projects would have been unlikely candidates for NSF support without a dedicated funding stream. I then review key features of DEL which distinguish it both from the Linguistics program and from other programs with NSF, showing that the innovations facilitated by DEL are largely unique to this program and not replicated elsewhere within NSF, nor in other funding agencies (cf. Holton and Seyfeddinipur 2018). Extrapolating from these examples I conclude that there is still a need for a distinct DEL program. Whether or not the world’s languages are still in crisis, there remains much work to be done. We are far from completing the work of documenting the world’s languages; there is still great need for new tools and infrastructure for language documentation; and there is much yet to do to build capacity for undertaking documentation work.

Fall 2017

Wednesdays 3-6 pm , Moore 224

This course provides an introduction to the study of the complex inter-relationships between language, landscape, and space.

Fall 2019

Wednesdays 3-6 pm , Moore 575

This is a seminar course which introduces students to the field of biocultural diversity and conservation, emphasizing transdisciplinary approaches to understanding the interrelationships between culture, ecology, and language. This course features lectures and discussions by key UH Mānoa faculty in anthropology, biology, botany, Hawaiian studies, natural resources, linguistics, literature, law, and more.

Spring 2020 (CRN: 81799)

Wednesdays 3-6 pm , Moore 226

This course will equip graduate students to carry out linguistic fieldwork, building on previous documentation and description where available.

Fall 2020 (CRN: 79286)

Wednesdays 4:30-6:00 pm (note revised start time) , online and video conference

This course will equip graduate students to carry out linguistic fieldwork, building on previous documentation and description where available.

Fall 2020 (CRN: 81099)

Tues / Thurs 1:30-2:45 , Online and video conference

Language typology deals with how and why the elements of language interact and function. Students acquire a broad overview of the grammatical make-up of languages in general and understanding of functional-typological linguistics.

Spring 2021 (CRN: TBA)

TBA , Online and video conference

Global perspectives on the threats to human linguistic diversity; the value of linguistic diversity to communities, linguistic science and humanity; and efforts being undertaken to reclaim Indigenous languages.

Spring 2021 (CRN: 94809)

Wednesday 4:30-6:00 pm HST , virtual

This course will equip graduate students to carry out linguistic fieldwork, building on previous documentation and description where available.

Fall 2021

Wednesday 3:00-5:30 pm HST , virtual

This course provides an introduction to the study of the complex inter-relationships between language, landscape, and space.

Spring 2023 (CRN: 87243)

Tuesday/Thursday 3:00-4:15 pm HST , Sakamaki B103

This course provides an introduction to the study of the complex inter-relationships between language, landscape, and space.

Fall 2023 (CRN: 78783)

Tuesday/Thursday 10:30-11:45 am HST , Kuykendall 208

A course in creating, accessing and utilizing enduring and comprehensive records of language in use.

Spring 2024 (CRN: 87715)

Mondays 3:00-5:30 pm , Moore 203

This course provides an introduction to the study of the complex inter-relationships between language, landscape, and space.

Fall 2024 (CRN: 79062)

Tuesday and Thursday 10:30-11:45 am HST , Bilger 319

This course is a hands-on introduction to the theory and practice of historical linguistics.

Fall 2025 (CRN: 79629)

Tuesdays 1:30-4:30 pm , Sakamaki D101

This is a seminar course which introduces students to the field of biocultural diversity and conservation, emphasizing transdisciplinary approaches to understanding the interrelationships between culture, ecology, and language. This course features lectures and discussions by key UH Mānoa faculty in anthropology, biology, botany, Hawaiian studies, natural resources, linguistics, literature, law, and more.

Fall 2025 (CRN: 77925)

Monday and Wednesday 9:00-10:15 am HST , Kuykendal 408

This course is a hands-on introduction to the theory and practice of historical linguistics.

Fall 2025 (CRN: 75669)

MWF 12:30-1:20 pm HST , Moore 103

This course is a hands-on introduction to the theory and practice of historical linguistics.

Spring 2026 (CRN: 88637)

Thursday 3:00-5:30 pm HST , Moore 112

Introduction to lexicography for minority and endangered languages.

Spring 2026 (CRN: 82020)

Tuesday and Thursday 10:30-11:45 am HST , Moore 228

Introduction to morphological phenomena and traditional approaches to morphological analysis, particularly those concerning the interfaces between morphology and syntax and phonology.