Spatial Orientation in East Nusantara

The Austronesian languages are well-known for the prevalence of geocentric systems of spatial orientation which use geography rather than ego as a reference point—most notably the distinction between ‘seaward’ and ‘landward’ This basic system has deep antiquity and can be reconstructed for Proto-Austronesian.

“the most general principle of macro-orientation in Austronesian languages is the land-sea axis, associated with the PAN terms *daya ‘toward the interior’ and *lahud ‘toward the sea’” (Blust 2009: 311)

However, within the region of East Nusantara—straddling the Wallace Line separating Western Indonesia and New Guinea—one finds a surprisingly large diversity of geocentric orientation systems. The Spatial Orientation in East Nusantara project seeks to understand the encoding of spatial relations in multiple domains across both the Austronesian and non-Austronesian languages of this region.

An initial survey of 155 languages conducted by Holton & Pappas identified six distinct types of spatial orientation systems in East Nusantara, each with numerous variants and hybrids. For example, Aralle-Tabulahan, a language of South Sulawesi, employs both an elevation system distinguishing high, level, and low; as well as a riverine system distinguishing ‘upstream’, ‘downstream’, and ‘across’. More details can be found in Holton & Pappas 2019.

(Holton & Pappas, 2019, to appear)

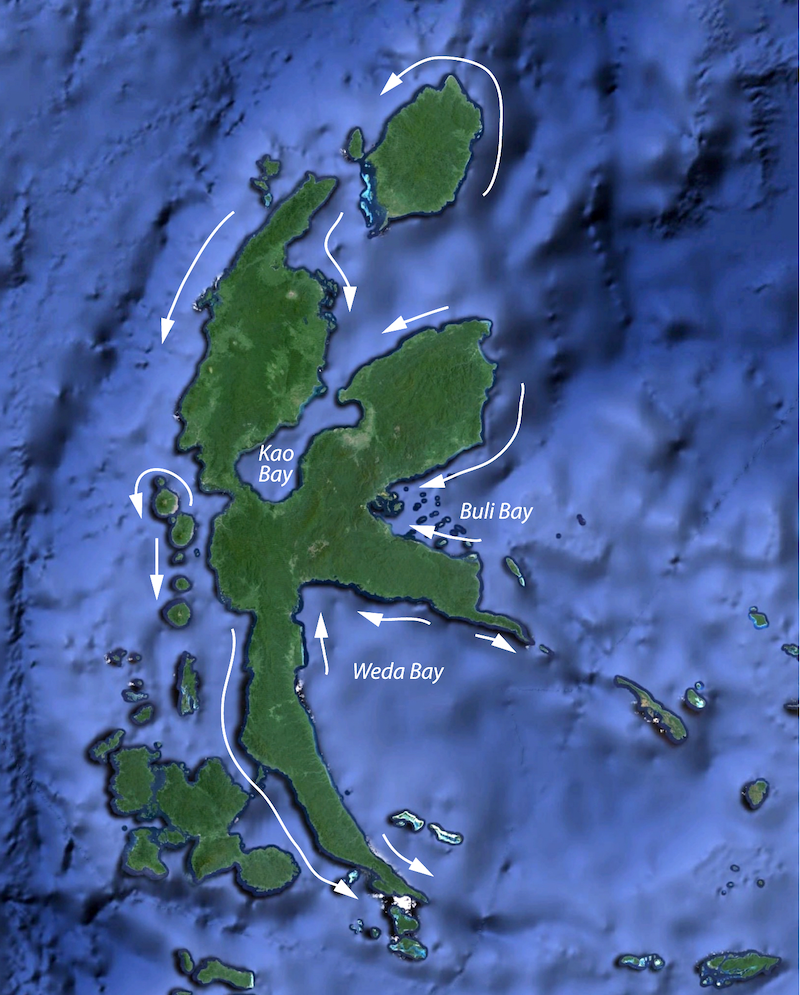

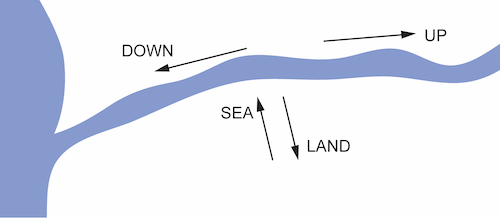

On the other hand, Spatial orientation also exhibit area patterns. This is particularly true in the region of Halmahera and surrounding islands. Here, a unique spatial orientation system has developed which contrasts a seaward-landward (or toward vs. away from water) axis with an orthogonal upcoast-downcoast axis. Most significantly, this system is shared across both the Austronesian and non-Austronesian languages of the region, and for any given location, the orientation of the upcoast-downcoast axis remains fixed regardless of the language employed. Yet, while the orientation of the coastal axis is fixed locally, it varies significantly across the archipelago.

In some areas the upcoast direction is the one’s left when facing the water, while in others it is to the right. From a linguistic viewpoint the choice of orientation for the coastal axis appears arbitrary. Three types of explanations have been proposed this distribution:

- Hydrographic: ‘upcoast’ is the direction against the prevailing current

- Migratory / Historical: speakers bring orientation systems (in whole or part) with them when they migrate

- Social / Cultural ‘upcoast’ (or ‘downcoast’?) is the direction toward the social center

The most popular of these is the social explanation. However, as noted by Holton (2018), various authors have proposed both ‘upcoast’ and ‘downcoast’ as being the direction toward the “social center”:

“[sultanates are] places to which tribute, in the form of goods and labor, historically flowed. Thus in the local system, these places are thought of as DOWN” (Allen and Hayami-Allen 2002:30)

“one travels down to the social centre” (Bowden 1997)

“the upward domain is thus both socially and morally distinct from the rest of social space” (Bubandt 1997:147)

“actually it is rather peculiar that Ternate is indicated as ‘down’ in spite of the age-long dominion of this former kingdom over South Halmahera.” (Teljeur 1987:351)

A more economical explanation is that the present-day coastal axis derives from an original riverine orientation system, where ‘upriver’ is equated with the direction ‘into the bay’. This explanation not only accounts for the orientation of the coastal axis in the vast majority of coastal locations, it also explains the usage of the orientation system in the interior. Here, the ‘upcoast-downcoast’ axis is orientated along the river and the ‘seaward’ and ‘landward’ indicate directions toward vs. away from the river, respectively.

One of the greatest challenges for understanding spatial orientation systems in East Nusantara remains the paucity of available data. Because orientation systems are embedded within local geography, in order to understand their function it is necessary to know not just the forms of the orientation terminology, but also their meaning across a range of geographic contexts. Without knowing how a system functions in different geographic contexts and at different scales, it can be difficult or impossible to disambiguate meanings. For example, in a region with a mountain range that lies to the north, a term which indicates direction toward the mountains could be equally well interpreted as ‘landward’ or ‘uphill’ or ‘upriver’ or simply cardinal ‘north’. Only by asking what happens on the other side of the mountains can we distinguish these potential meanings.

Ongoing research by this project seeks to fill gaps in these data through first-hand field work, while also seeking a broader synthesis and historical context for the evolution of spatial orientation systems.

References

- Pappas, Leah and Gary Holton. in preparation. Social and geographic predictors of spatial orientation typology in Austronesian languages . Linguistics Vanguard.

- Holton, Gary and Leah Pappas. to appear. Spatial orientation in the Malayo-Polynesian languages outside Oceanic. The Oxford Guide to the Malayo-Polynesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar, ed. by Sander Adelaar and Antoinette Schapper.

- Holton, Gary. 2017. A unified system of spatial orientation in the Austronesian and non-Austronesian languages of Halmahera. Language Contact and Substrate in Wallacea, ed. by Antoinette Schapper. NUSA 62.159-91.